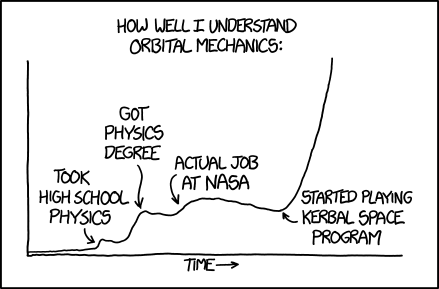

Randall roughly plots how high school physics, undergraduate-level physics and a job at NASA somewhat increased his knowledge of orbital mechanics. But this learning was apparently nothing compared to the "direct" experience of playing Kerbal Space Program, a rocket building and piloting sandbox game.

Orbital mechanics can be somewhat counterintuitive. The art of changing orbits involves relative velocities, positions, and times in complex interactions. As soon as you try deviating from a perfectly regular orbit, or start having to deal with N-body problems and orbital resonances, you have to coordinate your movements in possibly counterintuitive ways. One example is that if you want to reach an object ahead of you, on the same orbit, you actually have to 'brake' to reach a lower orbit. Once at that lower orbit, your angular velocity is faster, and you can start to overtake your target. After that manoeuver, you then have to accelerate to increase your orbital altitude again, which will end up reducing your angular speed so that you intercept your target.

At the title text Randall admits that at the time when he did work at NASA he was not involved in orbital mechanics—which is also true for most other NASA employees—but everybody was talking about this which in the end did increase his knowledge a little, as can be seen in the curve after the Job at NASA arrow.