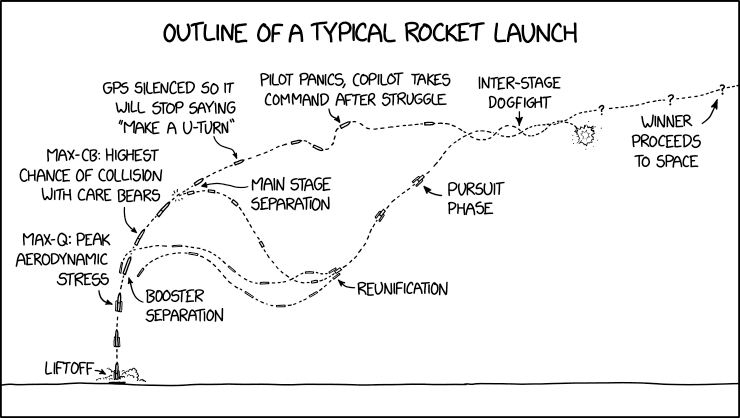

This comic was posted on a week with a notably high number of rocket launches. Originally, there were to be four orbital rocket launches from the United States on December 19, 2018 (the publish date for the comic), which would have tied with the prior record for number of orbital rocket launches in one day. While these launches were ultimately delayed, breaking the event, the comic was doubtless under production by then.

Only some of the steps listed are actually typical.

- Liftoff

- The traditional start of a launch, when the rocket leaves the ground. The engines will typically have been ignited a short time before, often one-by-one in a specifically engineered sequence to reduce shock stress on the rocket, but need to throttle up to produce enough thrust to overcome the rocket's weight. Some launch pad configurations physically restrain the rocket (at least to some degree) until the engines are known to produce the required thrust then the rocket is released (e.g. by pyrotechnically crushing restraining bolts such as in NASA Space Shuttle configuration, or by hydraulic actuators opening a sturdy "clamp", such as in SpaceX Falcon 9 configuration). "Liftoff" refers to the moment this happens, making the rocket lift off the ground.

- Max-Q: Peak aerodynamic stress.

- A rocket accelerates from the moment it leaves the ground. The faster a rocket goes, the bigger volume of air it pushes through per second - but the higher a rocket goes, the thinner the air. (Before liftoff, the rocket is not moving, and thus is not pushing through air. Once in orbit, there is essentially no air to push through, so the rocket is not pushing through air. Between those two times, the rocket is pushing through some amount of air, the exact amount increasing before Max Q and decreasing after Max Q.) "Max Q" is the moment where these two factors produce a maximum, and is the point where the rocket's structure must withstand the most air pushing back against it.

- Booster separation

- Rockets are designed in stages, so they do not have to carry the empty fuel tanks all the way to orbit. (Carrying any mass to orbit is expensive, so the more that can be dropped off earlier, the better.) Two or three stages are typical. "Booster separation" marks the point where the first of these stages (the "booster"), its fuel expended, is typically ejected.

- Max-CB: Highest chance of collision with Care Bears.

- This is entirely fictitious. Care Bears are fictitious characters, which have a toy line, television series, and movies. The existence of a basketball sneaker named the "Nike Air Force Max CB" may or may not be relevant.

- Main stage separation

- See "booster separation" above. This marks the point where the second stage (the "main stage") is ejected.

- GPS silenced so it will stop saying "Make a U-turn"

- Again, this is fictional. While some rockets do make use of signals from the Global Positioning System ("GPS"), no rockets are known to use the navigational devices that incorporate GPS readers and street maps, providing directions - often with optional text-to-speech - along the Earth's surface. Some such devices are notorious for getting confused when the processed signals become less reliable; constantly uttering "make a U-turn" would be one such confusion, and any device in such a confused state might well be silenced for being more annoying than helpful. Navigation of this nature is neither necessary nor useful on a rocket, which will have its entire route from ground to orbit computed before launch, and piloting typically left entirely to computers given the precise timing required and typically alternate inertial tracking and/or radio-triangulation signals providing feedback as to how true the track up to, then in, orbit has been. Altitude uncertainty tends to be greater than 'horizontal' position, and this sensitivity would degrade significantly as a receiver approaches the altitude of the particular satellites being listened to. GPSs uttering "make a U-turn" have been previously mentionned in 1837: Rental Car.

- In civil GPS receivers, it may also be a direct result of the CoCom restrictions baked into the firmware/hardware to prevent their use in high-speed/long-range weaponry (such as rockets) by hostile regimes. If space-launch equipment integrates GPS navigation at all, it would generally not be a retail device such as that bundled with a spoken prompt for road directions.

- Reunification (of boosters)

- Another fictional step. Discarded stages fall back into the Earth's atmosphere, either hitting the ground (or, more often, water) or burning up because of the heat-up resulting from high compression of air in front of them while re-entering thick layers of atmosphere at extreme speed. The booster and main stage would not be on a course to come anywhere near each other, and would not have enough fuel to change their course (running out of fuel being why they were discarded in the first place). Even if they did, landing for reuse (as SpaceX has attempted, often successfully) would be far more likely than a mid-air reunion.

- Pilot panics, copilot takes command after struggle

- Another fictional step. Astronauts are not the sort of people who panic easily, nor struggle with their crewmates. More importantly, in any modern rocket the "pilot" is not a human being, but a computer incapable of panic[citation needed] (as in the human emotion). It is possible that part of the flight computer could fail, causing redundant failsafes to take over, but the process could not correctly be described as a "struggle", and in any case this sort of failure is uncommon enough that it is not part of a "typical" rocket launch.

- Pursuit phase

- Fictional. This assumes the (nonexistent) reunified booster would have enough fuel to pursue the top stage of the rocket, and a reason to do so. See "Reunification". This might be a reference to Pursuit guidance. The comic indicates that a fight ensues with only one of the pair continuing to orbit.

- Inter-stage dogfight

- Fictional. See "Pursuit phase". A dogfight is an aerial battle between fighter aircraft, conducted at close range. This step claims that the rocket booster and the top stage of the rocket engage in a battle.

- Winner proceeds to space

- Fictional. As noted above, in a real rocket launch there is no dogfight of which there can be a "winner". A careful reading would note that the bottom stage "wins" by default; in contrast, in a real (orbital) rocket launch, the top stage typically proceeds to space.

The title text refers once again to the Care Bears franchise. The Care Bears live in a castle made of clouds, called Care-a-Lot Castle, so the comic claims that NASA aims to avoid launching into their castle, but sometimes cannot avoid hitting "stray" Care Bears. That being said, the point about the strike has a basis in truth; at the speeds a rocket moves, impact with something roughly the size and weight of a human (or a Care Bear) has the potential to be catastrophic. If something should threaten to connect with the rocket, the best that the humans involved can do is hope for a glancing blow with a part of the rocket sturdy enough to endure the impact.