Launch Risk

Don't worry--you're less likely to die from a space launch than from a shark attack. The survival rate is pretty high for both!

Don't worry--you're less likely to die from a space launch than from a shark attack. The survival rate is pretty high for both!

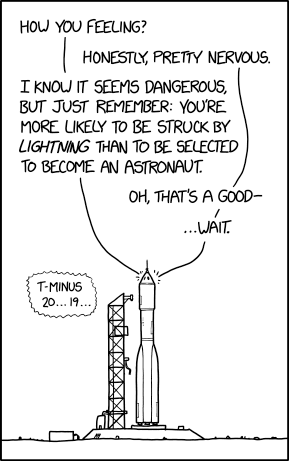

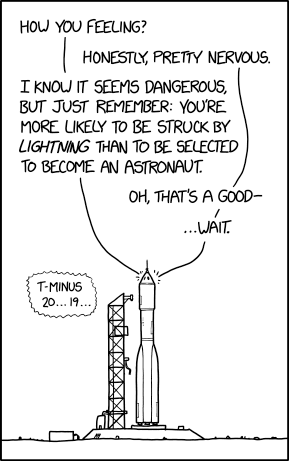

This comic deals with the faulty application of general statistics based on a large population, such as all Americans, to specific situations with vastly different statistics, such as astronauts.

A manned rocket ship is about to be launched into space. Mission control counts down from "T-minus 20," where "T" stands for the time at which the rocket is scheduled to launch. In the capsule, one astronaut asks another how they are feeling. The second admits that they are nervous. The first one offers a supposedly reassuring observation that they are more likely to be struck by lightning than to be selected to become an astronaut. Such comparisons are commonly used to illustrate that a particular probability is very small, and therefore not worth worrying about.

The second astronaut is about to agree that they have a good point, but then realizes the problem with their argument: the likelihood of being selected as an astronaut is a moot point, because they both already are astronauts. The comparison ignores the relevant concern, which is the danger involved in being an astronaut and launching into space. It may also provoke a false understanding that, given two events each with given likelihoods of happening, where chance has proven sufficiently provident enough for the less likely one to have occurred, the 'luck threshold' has been exceeded enough to make the more likely one now a practical certainty (a variation upon the hot hand fallacy, though with nominally independent events and opposing desirabilities).

The second astronaut's nervousness is understandable as space missions are historically quite dangerous, and have numerous avenues for potentially fatal failure, certainly far beyond the minuscule risk of being struck by lightning, approximately 1 in 14,600 throughout your entire life.

The title text creates additional confusion by referencing another common statistical reference point, the probability of dying in a shark attack. In addition to shark attacks being uncommon, they are also less likely to kill their victim than is commonly assumed. Still, while shark attacks are more frequently fatal than rocket launches, this comparison is once again useless, as the astronaut is not in any danger of sharks, but is literal seconds from launching into space. The astronaut is presumably not especially reassured by the "pretty high" survival rate.

Of the 557 people who who had been in Earth orbit (as of the time of this comic) 18 (3%) have died in related accidents, not specifically at launch (List of spaceflight-related accidents and incidents, Astronaut/Cosmonaut Statistics). Of the 93 incidents logged for 2018 in the Global Shark Attack File, 4 (4.3%) were fatal, but the statistic has been higher in the past when there was likely less education against provoking sharks.

A large metal rocket, such as depicted would be more likely to be struck by lightning than nearby structures. However launch controllers generally monitor weather carefully to reduce the chances of attempting to launch when lightning is likely.

A spacecraft launch can also trigger lightning, by creating a conductive path through electrically charged clouds. Apollo 12 was struck by lightning twice during the launch phase. Thankfully backup systems allowed the flight to proceed. For more information, see NASA: Lightning and Launches

The perceived value of risk is a recurring topic and is also featured in 795: Conditional Risk and 1252: Increased Risk.