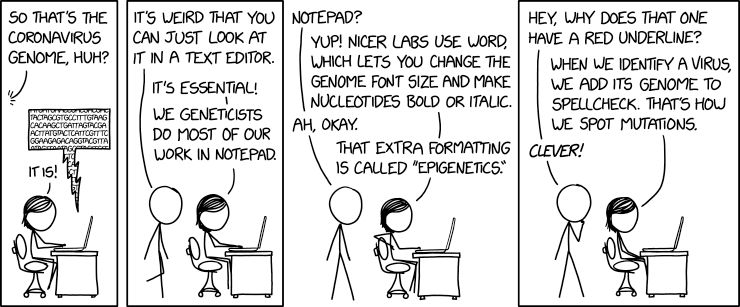

Coronavirus Genome

Spellcheck has been great, but whoever figures out how to get grammar check to work is guaranteed a Nobel.

Spellcheck has been great, but whoever figures out how to get grammar check to work is guaranteed a Nobel.

This comic is another comic in a series of comics related to the COVID-19 pandemic and was followed in the next comic by 2299: Coronavirus Genome 2. Megan is a geneticist doing research on the SARS-CoV-2 virus. She is analyzing the virus's genome, its genetic material composed of RNA. The genomic sequence can be represented as a list of nucleotide bases (guanine, adenine, cytosine, thymine, and uracil (often abbreviated as G, A, C, T, and U).

The nucleotide sequence displayed is a 100% match to six SARS-CoV-2 sequences in public databases, all of them originating from the East Coast of the United States. The sequence is from nucleotides 26202-26280 of the virus genome and overlaps an unknown open reading frame/gene named ORF3a. One of the matching sequences is [1]. However, SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus, and so its genetic material (not containing any DNA) would not include thymine (T) but would use uracil (U) instead. The sequence uses the codes of DNA as RNA sequencing involves copying the genome into a DNA, and the DNA code is more familiar anyways.

Cueball is surprised that Megan and her colleagues actually use Microsoft Notepad, a simple text editor, to look at the genome, instead of more modern technology. She explains that better research institutions use Microsoft Word, a more advanced editor, to allow additional formatting (such as bolding and italics), and humorously calls this "epigenetics". In the real world, epigenetics is the study of changes that are not caused by changes in nucleotides, but by chemical modifications of DNA or chromosomes that cause changes in patterns of gene expression and activation, sometimes several generations down. This might be considered analogous to altering the meaning of a text by changing its formatting rather than the content; for example, content can be moved into parentheses or footnotes to be de-emphasized, or rendered in boldface or enlarged to attract attention and emphasize key points. Much as text can be wrapped in HTML tags or similar markup to change its formatting, nucleotides can be methylated to prevent transcription, and the histones around which DNA is wound can also be modified to promote or repress gene expression. During DNA replication, these modifications are often also reproduced.

The real punchline comes when Megan uses spellcheck to detect mutations in the genome by adding the previous genome to spellcheck and comparing them. Overall, Megan uses ridiculously and humorously crude methods to analyze a major genetic item. The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is almost 30,000 base-pairs long, which exceeds the longest words of any natural language by two orders of magnitude (the longest words ever used in literature -- i.e. not constructed in isolation simply for the purpose of being a long word, or chemical formulas -- approach 200 letters), and may exceed the capabilities of any available spell-checking program. Furthermore, a spellcheck program underlines the whole word if a single letter is wrong and not just the letter itself. Thus, it would not be able to highlight individual mutated base pairs. Megan might be better served by using a diff tool, but most scientists generally use commercial software that is designed to view, annotate, and edit DNA sequences (eg: Snapgene, Geneious, DNAstrider, ApE).

The title text mentions grammar checking and claims that whoever discovers how to use that to compare genomic material should be awarded a Nobel Prize. Spell-checking is analogous to comparing sequences against ones previously known, an activity that is the bread and butter of bioinformatics nowadays. Grammar checking would be analogous to having some sort of sense as to how well all the sequences generally cooperate and interact to create possibly viable functionality in an organism, something we are unable to do at the moment except in very limited ways and only in a few simple cases. It may also be a snarky commentary on the untrustworthy nature of grammar-check programs in general, which often follow grammatical rules far more strictly than is practical; it's not uncommon for an author to follow a grammar-check recommended correction only to find the corrected portion is now part of a longer portion that the checker deems "incorrect".