Physics Cost-Saving Tips

I got banned from the county fair for handing out Helium-2 balloons. Apparently the instant massive plasma explosions violated some local ordinance or something.

I got banned from the county fair for handing out Helium-2 balloons. Apparently the instant massive plasma explosions violated some local ordinance or something.

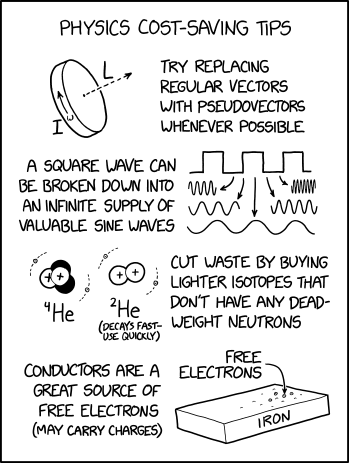

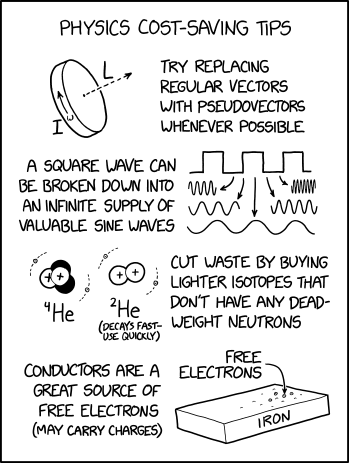

This is another one of Randall's Tips, this time with a series of Physics Cost-Saving Tips. It also continues the previous 2648: Chemicals comic's jocular theme of tricks to supposedly save money based on misinterpretations of science.

It suggests four ways to reduce costs or provide something for free for physicists to save money on their research. For instance getting free electrons from a conductor or replacing regular helium with helium 2. None of these would provide any real advantages even when possible to implement, and could even be very dangerous, see below in the table. Obtaining money from physics experiments was also described in 2007: Brookhaven RHIC.

In the title text, Randall claims to have been banned from the county fair for handing out helium-2 balloons because of the instant massive explosions caused by its radioactive decay (that helium-2 decays fast is mentioned in the comic, with a joke suggestion to use it quickly). He jokes that the balloons violated a local ordinance. Helium balloons are often given out at county fairs and similar events, but they are filled with helium-4 and therefore inert (a very small part will be helium-3, 2 ppm). A balloon filled with helium-2 is a practical impossibility because of its nanosecond half-life. Assuming a 12-inch diameter balloon at 1 atmosphere of pressure, the balloon-bomb would have a yield of roughly 17 tons of TNT equivalent.

Calculations Helium-2 has a half-life of roughly 10-9 seconds, or one nanosecond, and a mean life of roughly 1.44 nanoseconds. For context, light travels at roughly 30 cm per nanosecond. This means that on a human scale the energy is released all at once, and we only have to calculate total energy released, and not worry about time taken.

Helium-2 decays through 99.99% proton emission. For simplicity's sake, we'll call that 100%. Helium-2 is formed from two hydrogen-1s, and 1.25 megaelectron-volts, or as an equation,

H +

1 1 H + 1.25 MeV =

1 1 He. It therefore follows that decay from a helium-2 atom to two hydrogen-1 atoms would release 1.25 MeV,[citation needed] per the conservation laws of energy and mass.

2 2 A moderately-sized balloon might have a diameter of 12 inches. Some calculations give this a volume of roughly 14.83 liters (assuming a spherical balloon.) If the balloon is at 1 atmosphere of pressure at 25 degrees Celsius, then there would be 0.6058 mol in the balloon, mean that there is 0.6058 * 6.022×1023 atoms, or 364,800,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms.

To recap, a helium-2 atom decaying results in 1.25 MeV of energy, and there are roughly 365 sextillion atoms in a balloon.

Every atom will create 1.25 MeV of energy, and therefore 365 sextillion atoms will create 365*1.25 sextillion, or 456 sextillion MeV. Interestingly, this is equal to 456 nonillion electron volts, or 4.56 megayottaelectron-volts. 456 sextillion megaelectron-volts is also equal to roughly 73,100 megajoules, or 17.4 tons of TNT equivalent.

The smallest nuclear bomb, the W54, had a yield of between 10 and 1,000 tons of TNT. The largest conventional bomb, the GBU-43/B MOAB, has a yield of roughly 11 tons. The 2020 Beirut explosion was roughly equivalent to 500 tons. So, while the helium-2 balloon bomb would be larger than all conventional bombs, it would still be smaller than most nukes. Handing out what are effectively small atomic bombs at a county fair would not go down well with any surviving local authorities,[citation needed] so merely being banned is a very mild punishment. Criminal charges such as mass murder and terrorism would be more likely if it weren't for the absurd impossibility of the scenario.

The title text is likely also a pun, as the word "ordinance" means a local law, and the very similar sounding word "ordnance" means artillery and other explosive weapons, which the balloon would qualify as.

Table of tips

Cost-Saving Tip Explanation Try replacing regular vectors with pseudovectors whenever possible  Relationship of pseudovectors torque (τ) and angular momentum (L) to "regular" Euclidean vectors position (r), force (F), and linear momentum (p) in an oscillatory rotating system. Not shown is the centripetal force of the spoke's tension, a Euclidean vector towards the axle proportional to linear momentum, converting it to angular momentum.

Relationship of pseudovectors torque (τ) and angular momentum (L) to "regular" Euclidean vectors position (r), force (F), and linear momentum (p) in an oscillatory rotating system. Not shown is the centripetal force of the spoke's tension, a Euclidean vector towards the axle proportional to linear momentum, converting it to angular momentum.The prefix "pseudo-" refers to an inauthentic variation of something. Fakes are usually cheaper than their original brand-name product, while often working just as well, so the comic implies a pseudovector could be a less expensive substitute for a regular vector. On the contrary, pseudovectors, or axial vectors, are distinct from regular Euclidean vectors, which have a magnitude and direction (velocity, for example). Pseudovectors are usually being involved with rotation or physical effects that share properties with rotation, similar to the relationship between angles and lengths. Pseudovectors are formed from the cross products of Euclidean vectors, in three dimensions, and while similar to Euclidean vectors, there is no physical meaning to their specific direction, only their magnitude and portions of their position. For example, angular momentum is described by a pseudovector, labeled L in the comic, normal to the plane of rotation, originating from the center of rotation, with magnitude equal to the angular velocity of rotation ω multiplied by the moment of inertia I. (The comic's diagram is drawn according to very uncommon left-handed coordinates instead of the standard right-hand rule. Randall is right-handed.[1])

A square wave can be broken down into an infinite supply of valuable sine waves Fourier analysis can decompose any periodic function into a series of sine waves. A square wave is equal to the sum of an infinite series of sine waves. However, the sine waves are not removed or separated individually, so such a Fourier transform does not produce a "supply" of sine waves for practical use in any tasks other than analysis, and as abstract mathematical objects are exempt from the laws of supply and demand (most of the time), Cut waste by buying lighter isotopes that don't have any dead-weight neutrons Chemical elements are identified by the number of protons in each atomic nucleus, equal to the number of electrons in their shell (unless the atom is ionized), which dictates most of their chemical behavior. Isotopes are variants of the element with different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus, among which chemical behavior is usually nearly identical. The comic suggests that the neutrons don't serve any useful purpose, so, in theory, if purchasing an element by weight, and its isotopes have the same price per unit weight, then you can save money by buying isotopes with no neutrons at all. In reality, the cost per unit weight for material containing a larger concentration of normally rare isotopes, such as heavy water or enriched uranium, is much higher than the cost of material containing isotopes in their ordinary proportions. (An exception is depleted uranium, which costs less than regular uranium because it is a byproduct of the production of enriched uranium.) In addition, a certain range of neutron quantity is needed to keep atoms stable, as atoms with too many or too few neutrons will decay more quickly than the common isotopes. The image shown is helium-2, an isotope of helium which has a half-life of less than a nanosecond. It decays into two ionized hydrogen atoms, releasing a large amount of energy—hence the explosions mentioned in the title text. Conductors are a great source of free electrons (may carry charges) Free electrons are electrons that are not tightly bound to specific atoms so they can move freely, such as in conduction bands of the metallic bonds throughout the iron ingot depicted in the comic. Randall interprets "free" in a different sense, meaning no cost. The charges free electrons carry are electric, not monetary as implied by the pun. Ordinary matter usually contains electrons, but although the dielectric layer of a capacitor can collect electrons, it is not easy to store pure electrons, as they repel each other. When a solution has free electrons, it becomes alkaline (basic) and corrosive. Randall has explained the problems with collecting a large number of electrons before.