Stargazing 4

We haven't actually seen a star fall in since we invented telescopes, but I have a list of ones I'm really hoping are next.

We haven't actually seen a star fall in since we invented telescopes, but I have a list of ones I'm really hoping are next.

This is the fourth comic in the Stargazing series, following 2274: Stargazing 3 which came out five years before. That was the longest time between two comics in the series so far.

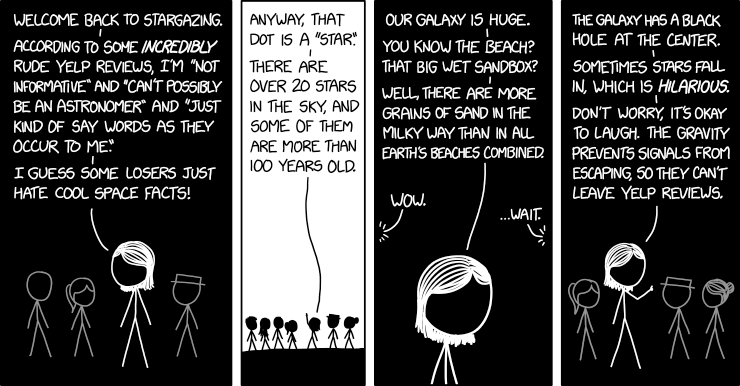

The host Megan begins the introduction by referencing negative reviews of her stargazing lessons on Yelp, a popular site for rating businesses such as restaurants. The reviewers doubt that she is actually a qualified astronomer due to how simplistic her lessons are; they claim she is just saying the words that come to mind. She denigrates these people as people who "hate cool space facts", as opposed to being people who hate virtually useless space facts.

Then she states that there are over 20 stars in the sky and some of them are over the age of 100. Both of these statements are literally true, but extreme understatements.

- A few thousand stars are visible to the unaided eye under good viewing conditions, though in a city there could be less than 20 stars visible even on a clear night.

- For a normal stargazing session the event should be held in a venue with as little light pollution as possible, which could mean the middle of an urban green space, conveniently away from lighting or else specially arranging for the most inconvenient lighting to be off for the duration. However, given the unprofessional nature of Megan's lessons, there is no guarantee that this session does not take place under less-than-ideal circumstances. Or she is perpetually unlucky as daylight or clouds may further reduce visible stars.

- Ignoring the need for visibility entirely, it is also estimated that there are about 200 sextillion (2×1023) stars in the observable universe, of which around half would be somewhere 'in the sky' - that is, above the horizon - at any given moment from any place on Earth.

- Stars are typically billions of years old. While new stars are being created in nebulae all the time, it is extremely unlikely that we are seeing the nebulous start of even the shortest-lived stars within the first century of their life. One of the 'youngest' potential candidates is SN 1987A, which may be a neutron star less than 40 years old. But that is discounting the additional age it has acquired from it being approximately 168,000 light years away from us (making it actually 168,000+ years old). It is further undermined by arguably just being the next stage of life of the far older star that went supernova in order to leave the neutron star behind.

- Of stars within 100 light-years of Earth and formed afresh from interstellar material, AU Microscopii is slightly over 30 light-years away and considered to be very new as far as stars go. But it is still 22 million (...and thirty) years old by current understanding.

Megan states that our galaxy is huge and that there are more grains of sand in the Milky Way than grains of sand on all of Earth's beaches. This size comparison is a parody of the common saying that there are more stars in the visible universe than grains of sand on all the beaches of Earth. Since the Earth's sand is a subset of all of the galaxy's sand, and there are more planets with sand other than Earth (such as Mars), there are unquestionably more grains of sand in the Milky Way than on Earth. Tangentially, it is unclear whether the stars outnumber Earth's sands, as shown here: Do Stars Outnumber the Sands of Earth’s Beaches? and here: The ever-lasting question: more sand or stars?. Also, the original quote was all the sand on Earth, not just on the beaches. Megan adds a helpful hint, calling a beach a big wet sandbox.

She then finishes the lesson by correctly saying that there is a black hole in the center of our galaxy (Sagittarius A*), and that stars sometimes fall into and are consumed by the black hole. When stars come too close to black holes, they experience a tidal disruption event (TDE), where a star is pulled apart (spaghettified) by the black hole after passing its tidal radius, or Roche limit. This creates streams of material that orbit the black hole and form an accretion disk that will eventually be consumed by the black hole or ejected in jets.

She adds her personal opinion about this fact, saying that such events are "hilarious", and proceeds by saying that it's okay to laugh at the fate of those stars as the gravity of the black hole will prevent any signals from those stars escaping. This is due to black holes' immense gravitational attraction that prevents even light from escaping. In Megan's case the most important consequence of this fact is that anyone on planets around such stars cannot leave Yelp reviews if they hear her laughing. Thus, they cannot add to those that mock her lesson.

However, as the Roche limit of a black hole for the average star it's consuming is usually greater than the size of the black hole's event horizon (Schwarzschild radius), reviews made just after the star begins spaghettification could still escape the black hole. But not only do stars not use any kind of human-made technology,[citation needed] but any information regarding the app Yelp has yet to reach any star near Sagittarius A*, and will do so only after 27,000 years. It is much more likely that someone living on one of the star's planets would try to leave a comment on Yelp, not the star itself, but in any case the same issues with distances would of course apply. It also seems unlikely that any planet would still be following a star when it first gets that close to a supermassive black hole, or indeed that complex life could exist on such a planet in the first place due to high levels of high-energy radiation in the galactic core.

In the title text Megan claims that we haven't actually seen a star fall into the black hole since we invented telescopes. While it is true that we haven't observed any star fall into our closest supermassive black hole, this phenomenon has been been observed for other black holes, and the G2 gas cloud on an accretion course was discovered in 2002. Megan also apparently has a list of stars she would like to see fall into the black hole. But she can just keep hoping, as humans at present have no way of changing the position of any star, and probably couldn't implement it soon upon such distant stars even if were possible. So unless she is hoping for one (or more) of the already closer stars to be observed to fall in next, she is unlikely to experience success for stars on her list.